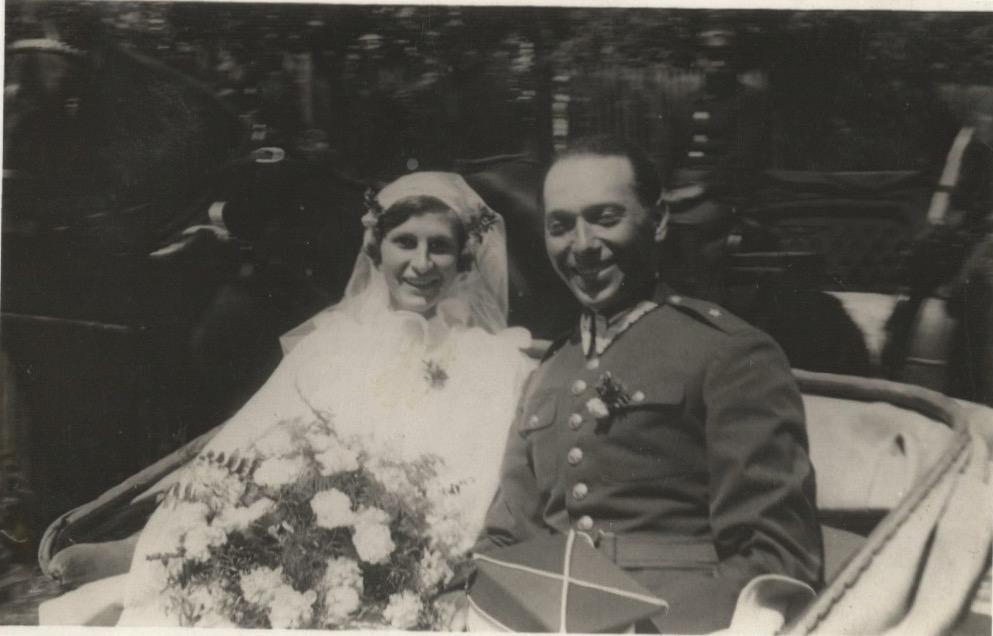

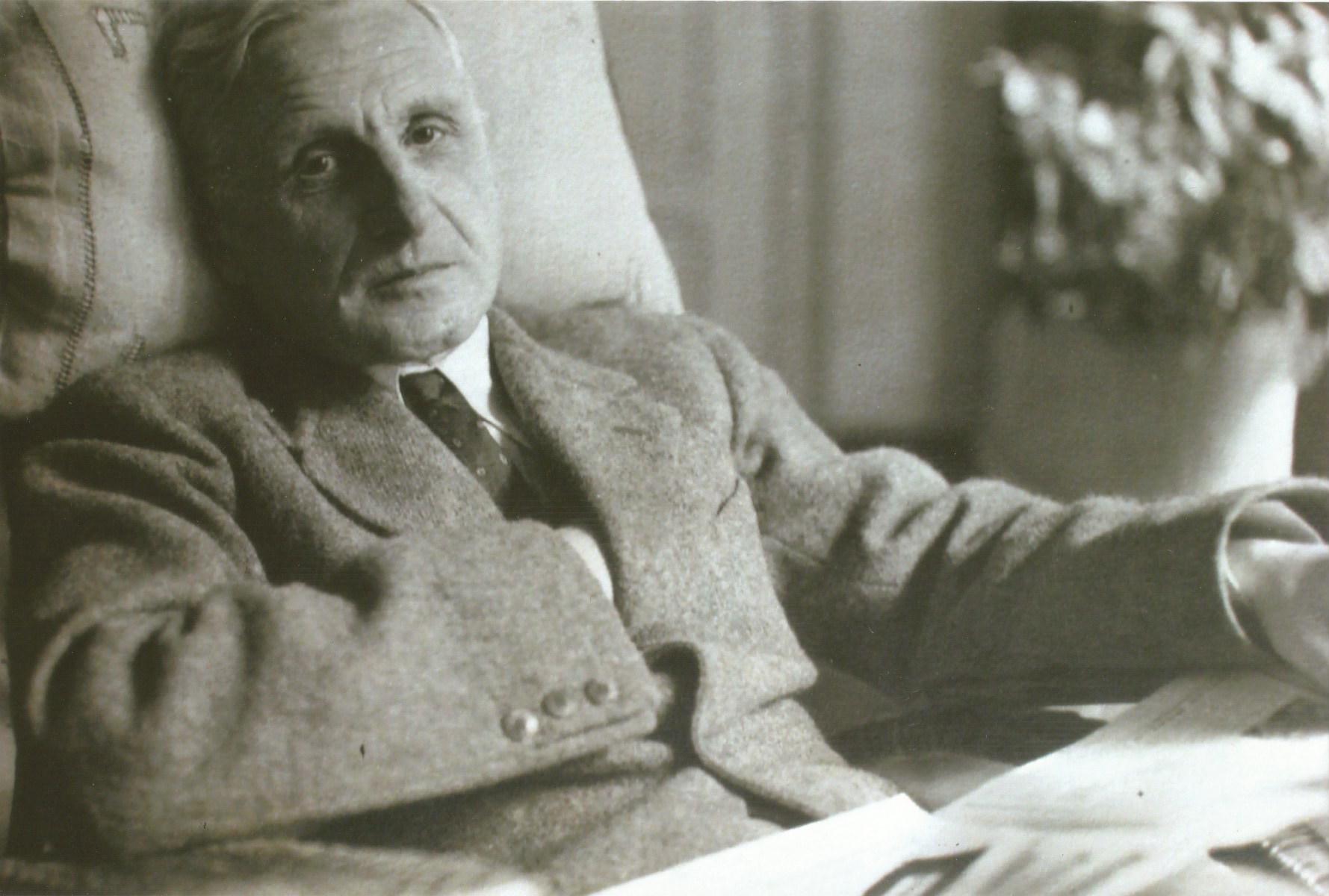

Exile is a stark and painful condition that can drive one to the brink of madness. In this borderland between the “what was” and “what will be” we can find our strength and make meaning out of it or collapse in despondency. Hearing Rose tell her stories again and again showed me that she had suffered exile and survived but in the end the damage done seemed to me not truly transformed. As at her deathbed, she pleaded time and again to my husband, “Don’t forget Wójcza. Promise me you won’t forget.” Clinging to the picture of the house that had been burned down, the house that held her happiest memories, the house that had the potential to bloom even fuller had the war not utterly destroyed everything, this was her dying memory: to not forget. Rose was not able to tell us why she felt so strongly about Wójcza, but as is the case with all narratives, there are some gap-filling opportunities which only the individual reader or observer can take advantage of. Some might say I am filling in the gap by my move to Poland as how do we know she would have intended this? The answer is: we don’t. We also don’t know if the disease itself and its profile would suggest a biochemical reason for early childhood memories to override later ones. But in the world of relationships, not all is known. Much, if not most, spawns from the unconscious. Here resides the mystery in this liminal space between two people. And between Rose and I prevailed the tenacious motif of exile.

In a blog article I wrote for her 89th birthday, I concluded with: “Love the Lord with all your heart, be happy be happy today”. This is what she would tell me. I love you Rose Kieniewicz. Thank you for being my mother-in-law, my Naomi, my Mara, my Rose, and my north star.

I wasn’t the only one in the family who likened the story of Ruth and Naomi to me and Rose. From the chapter Law and Narrative in the Book of Ruth, Zornberg writes: “Boaz acknowledges Ruth’s spiritual parentage: like Abraham, she has left her father and mother in her quest for an unknown alternative. She belongs to the world of Abraham, which for her is represented by Naomi. As a mother, however, Naomi is far from incarnating the soft mother of infancy. Her words create her as separate, distinct, not the loving mother of primal desire, but the mother whom Christopher Bollas describes as a process of transformation….The Ruth who is able to articulate her experience, to play in the potential space between desire and reality, is also the Ruth who seeks the transformative moment of uncanny fusion. It is at the hands of a somewhat austere mother, then, that Ruth seeks out her own transformation.

I cannot say Rose was austere though there was an austerity about her in her faith to God. There was an unknowingness about our relationship. She never asked me anything about my past or the reason I had chosen to leave family and friends so late in life. My exile was not forced, but self-imposed. Still, does the soul of one in exile recognise another in exile? Was her story so powerful and unfinished in those six years of caring for her that something of it permeated my own soul like a spirit? As her illness took her further and further away from me, I became the stranger. She stopped speaking English and her periods of withdrawal were more pronounced, yet I loved her with all my heart. I loved what she stood for. I loved her strength and I wanted to be strong like this. I wanted that only God should be my guide and not the capricious nature of man.