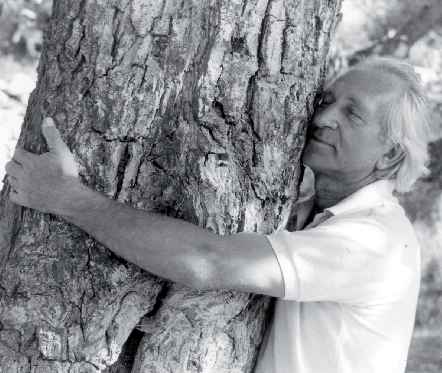

Henryk Skolimowski

Edited by Paul Kieniewicz

Philosopher and ecologist Henryk Skolimowski died in his hometown of Warsaw, Poland April 6, 2018. Henryk inspired generations of ecologists and conservationists. He was professor of philosophy at the University of Southern California, and the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor where he taught his system of eco-philosophy. The author of over two dozen books in English and in Polish, he conveyed the vision of the world as a sanctuary. He taught that a society must be grounded in its ecological context in order to grow and to flourish. He would refer to himself as “a dissident son of western civilisation”. This essay contains the kernel of his philosophy.

Forests and the primal geometry of the Universe

We all know how intricate the relationships are between trees and the life forms that surround them. But why are trees so important to human beings who are after all so different? Though distinctive and different, human beings are part of the same life heritage.

The reason why trees and forests are so important to us, human beings, is connected with the natural geometry of the universe. We must therefore distinguish between geometry thought up by man, stemming from Euclidean geometry, that we learn at school, from natural geometry, in particular the geometry of living forms.

When Euclid discovered his geometry, which became the basis for man-made forms, Greek reason was already corrupted by Aristotle’s approach to the world, of analysis and classification. The Greek world of Socrates and Plato still contained a unity and harmony. Since Aristotle, we start to divide and chop and atomize —put everything into separate compartments, giving them an identity with the help of special labels called definitions.

Euclid and his geometry only reinforces the tendency of separatism, thinking with the aid of logical categories. We start with axioms, then principles derived from axioms, finally theorems derived from axioms by accepted rules. Everything is precisely and rigorously defined. It’s a triumph of the rational Western mind which emphasizes the importance of formal reasoning, the importance of axioms, that then become the foundation for constructing the rest of the building. Let us pay particular attention to the emphasis that Euclid places on the point and the straight line. We know that we never see a point because it is as such, invisible. Similarly, in nature we never find a straight line. Yet the architecture of the human world, or more precisely the architecture of the world constructed by modern man, is founded on straight lines and those invisible points.

Let us put the proposition in general terms: the geometry that dominates our lives, whether we live in a city, in a modern house, or when we drive an automobile, is a geometry derived from an abstract system of a man-made geometry. It is a geometry which, after a while, constrains and suffocates us.

We have distinguished natural geometry from man-made geometry. But what is natural geometry? They are the forms by which and through which the universe and life has evolved. What are these forms? They are circular, spiral, round, womb-like. When we contemplate the architecture of the universe: the galaxies and atoms, amoebas and trees, then we immediately see that the dominant forms and shapes of nature and of the universe are round and spiral and so often amorphous.

The dancing universe does not move in straight lines. It moves in spiral, circular and irregular motions. The choreographer of dancing life in the universe is not the computer and its linear logic. The quintessential symbol of life is that of the womb.

All life has emerged from primordial womb which is irregular, amorphous, full of connecting loops and spirals. We, individual human beings, were conceived and formed in the wombs of our mothers. Natural geometry conditioned our early movements shaped our early development, formed our bodies which are ultimately an expression of this geometry. Now, look at your own body and see it in terms of natural geometry. It is full of irregular shapes — round, oval and asymmetrical. It’s hard to find any straight line within the architecture of our body. The head is such a funny irregular egg. The hands and legs are irregular cylinders. The eyes and the mouth, the neck and the stomach are but endless variations on the theme of natural geometry.

Nurtured, conditioned and shaped by natural geometry, we respond to it in an intuitive and spontaneous manner. Why do we rest so well in the presence of trees? Because being in their presence is for us a return to the primal geometry of life. That is why we feel so good in the act of communing with them. Being born and nourished by natural geometry we long to return to it. By dissolving ourselves into the geometry of a tree, we remove tensions and accumulated stresses thrust upon us by artificial geometry. The artificial geometry of man-made environments is full of tension and stress.

In returning to the forest, we return to the womb, not only in psychoanalytical terms but in cosmological terms. We are returning to the source of our origin. We are entering into communion with life at large. Forests provide for us a niche in which our communion with all life can happen.

The unstructured environment is necessary for our physical and mental health, as well as for those moments of quiet reflection, without which we cannot truly reach our deeper self. It should not be limited only to forests. Rugged mountains and wilderness areas provide the same nexus for being at one with the glory of elemental life forces. Wilderness areas are life-giving in a fundamental sense, nourishing the core of our being. This core of our being is sometimes called the soul.

To understand the nature of human existence is ultimately a metaphysical journey, at the very least a trans-physical one. In Greek, “metaphysical” actually means “trans-physical”. The metaphysical meaning of forests is based on the quality of space the forests provide for the tranquility of our souls. Those are spaces of silence, spaces of sanity, spaces of spiritual nourishment — within which our being is healed and at peace.

We all know how soul-destroying and destructive to our inner being modern cities can be. It’s enough to compare a corner of unspoiled nature with that of a city dominated by technology to understand the metaphysical meaning of forests, of mountains, or of marshlands.

Though trees are immensely important to our psychic well-being, not every tree possesses the same energy and meaning. Manicured French parks and primordial Finnish forests have very different qualities. In manicured French parks, we witness the triumph of Cartesian logic and Euclidean geometry. In Finnish forests, immensely brooding and surrounded by irregularly shaped lakes, we witness the triumph of natural geometry.

What is natural and what is artificial is nowadays difficult to determine. However, when we find ourselves among the plastic interiors of an airport, with its cold brutal walls and lifeless plastic fixtures surrounding us — on the one hand, and within the bosom of a big forest, on the other hand, we know exactly the difference and without any ambiguity. In the forest our soul breathes, while in plastic environments our soul suffocates.

The idea that our soul breathes in a natural unstructured environment should not be treated as a poetic metaphor. It is a palpable truth. One recognizes it on countless occasions, and in many contexts — although usually indirectly and semi-consciously.

We go to a lovely, old cottage. Our attention is drawn to old, wooden beams supporting the ceiling. It doesn’t happen that way with some concrete and iron beams. We go to a modern flat, undistinguished otherwise except that there is a lovely wooden paneling along the walls of the rooms. We respond to it. We resonate with it. We do so not because we are old sentimental fools, or for aesthetic reasons alone, but for deeper and more fundamental reasons.

We breathe more freely when there are other life forms around us. Those old beams made of oak in the old cottage breathe as does the wooden paneling in the modern flat. Plastic interiors, concrete cubicles, those tower blocks, and rectilinear cities do not breathe. We find them ‘sterile,’ `repulsive,’ depressing.’ These very adjectives come straight from the core of our being. And those are not just the reactions of some idiosyncratic individuals, but the reactions of at least a great majority of us.

A plastic interior may be pleasant in an aesthetic sense. Yet soon in our soul there awakens the feeling that it is uncomfortable, constraining and that in some way it cripples us. The primordial life in us responds quite unequivocally to our environment. We must learn to listen attentively to the beat of primordial life in us, whether we call it instinct, intuition, or a holistic response. We respond with great sensitivity to spaces, geometries and natural forms surrounding us. We respond positively to the forms which breathe life because they strengthen life. Life in us wants to be enhanced and nourished.

It is therefore very important to dwell in such a surrounding in which there are the forms that can breathe —wooden beams, the wooden floors, wooden paneling. Lucky are the nations that can build houses made of wood — inside and outside. For wood breathes, changes and decays, as we do. It is also important to have flowers and plants in our living environment. For they breathe. To contemplate a flower for three seconds may be an important journey of solitude, a return to primal geometry — which is always renewing. We make these journeys actually rather often, whenever plants and flowers are in our surroundings. But we are rarely aware of it.

Forests and spirituality are intimately connected. Ancient people knew about this connection and cherished and cultivated it. Their spirit was nourished because their wisdom told them where the true sources of nourishment lie.

Sacred forests in history

Ancient people lived closely with their environment. They weaved themselves into the tapestry of life surrounding them so exquisitely that we can only admire their sensitivity and their wisdom. They had a very special understanding of places, the locus genius of their territory.

Ancient people lived closely with their environment. They weaved themselves into the tapestry of life surrounding them so exquisitely that we can only admire their sensitivity and their wisdom. They had a very special understanding of places, the locus genius of their territory.

Forests were of course of great importance to ancient people, and everywhere in the world where trees grew, some forests were marked as particular spaces, indeed as sacred places. These forests had to be protected, and one could never desecrate them. In the seminal book of Sir James Frazer, The Golden Bough(1935), we have impressive and eloquent evidence how people, from the Paleolithic era onwards preserved and cared for their forests; how they treated them as sacred. “In them no axe may be laid to any tree, no branch broken, no firewood gathered, no grass burnt; and animals which have taken refuge there may not be molested!” 1

In the world of classical Greece, and then of Rome, these special groves and forests were usually enclosed by stone walls. This enclosure was called in Greek Temenos, an exclusive, demarcated place. A better translation would be ‘a sacred place.’ Indeed in the late 1970s, a periodical entitled Temenos started publication in England, explicitly evoking the spirit of Temenos — as a sacred enclosure, and calling for the creation of sacred spaces.

In Latin the term for these demarcated places was templum, the root of the word ‘temple.’ To begin with, those sacred enclosures were sanctuaries in which religious ceremonies took place. They were in fact temples under the open skies. When later on temples were erected as monumental buildings with columns and all, sacred groves and forests did not cease to exist. They were still cherished and protected. They inspired a sense of awe, of the mystery of the universe, a higher state of in-dwelling, of being close to gods. The Roman philosopher Seneca in the first century A.D. writes,

If you come upon a grove of old trees that have lifted their crowns up above and whose interlacing boughs have shut out the light of the sky, you feel that there is a spirit in the place; so lofty is the wood, so lonely the spot, so wondrous the thick unbroken shade2.

That perception of the mystery of the universe evoked in a particular way in those special places, led ancient people to celebrate and protect them. They felt their life was enriched and deepened there. In sacred groves and forests, they felt close to the gods and other sublime forces of nature. This sense of the mystery of the universe has, by and large, been lost by modern Western man.

When we go to Delphi, on a crisp spring day, at the time when the hordes of tourists have not yet desecrated the place, and when in peace and tranquility we can merge with the spirit of the place, we feel a tremendous power emanating from the surroundings.

The sense of the sacred resides in us all. But it now requires very particular circumstances for it to manifest. Our jaded bodies, our overloaded senses and minds all make the journey of transcendence, to the core of our being, rather difficult.

For ancient people the sense of the sacred was enacted daily. The whole structure of their lives was so arranged, that not only could they experience the sacred, but were encouraged to do so. This is difficult to do in our times.

In the sacred groves and forests of ancient Greece, particular species of trees were dedicated to particular gods. Oaks belonged to Zeus, willows to Hera, olives to Athena, the laurel to Apollo, pines to Pan, the vine to Dionysius. But that attribution was not rigid. The ancient Greeks were generous and flexible people. In various localities, due to local traditions, the same trees could be dedicated to different deities. On the island of Lesbos, for instance there was an apple grove dedicated to Aphrodite.

Many sacred groves contained springs and streams and sometimes lakes. The pollution of these springs and lakes was absolutely forbidden. There was usually a total ban on fishing, except by priests. It was believed that whoever caught fish in Lake Poseidon would be turned into the fish called “the Fisher” (Pausanias, 3,21,5).

In PeIlene there was a special sacred grove, dedicated to Artemis, which no one but priests could enter. But this was unusual. The common rule was that ordinary people could enter the grove providing they came ritually clean, meaning that they were not burdened by serious crimes, especially of spilled blood.3

The tradition of sacred groves and forests was maintained by ancient people throughout the world. Sacred groves in India are as ancient as the civilization itself. Indeed, they go back to prehistoric, pre-agricultural times. While the idea and the existence of sacred forests and groves has not survived in the West — as we have progressively become a secular society —in India those groves have survived until recent times. However, with the weakening of the religious structure of beliefs, the very idea, and along with it, the very existence of sacred groves and forests has been undermined also in India. Yet there are still some sacred groves in India left, particularly among tribal people.4

One of my favorite definitions of the forest is that given by the Buddha. For him the forest is “a peculiar organism of unlimited kindness and benevolence that makes no demands for its sustenance and extends generously the products of its life activity; it affords protection to all beings, offering shade even to the axe man who destroys it.”

Native Americans or American Indians are particularly sensitive to the quality of places. To worship a mountain, a brook or a forest is for them quite a natural thing, for every plant, every tree as well as Mother Earth and Father Heaven are imbued with spirit.

In the cosmos infused with spiritual forces, delineating special places as particularly important and sacred was both natural as it was inevitable. These special places were also the places of ritual and ceremony, in which the sacred was enacted in daily life. In that act, the essential mystery, and divinity of the universe was affirmed.

In the Western world, churches and shrines served this purpose, of connecting man with the sacred. But that was some time ago. As we became progressively secularized so we

lost the sense for the mystery of life and the sacredness of the universe. The churches are now hollow and reverberate with nothingness, for the spirit is gone from the people. Churches are being closed. In England alone two thousand of the existing sixteen

thousand churches have been closed. It is reported that only three percent of the people regularly attend the Anglican church. The Bishop of Durham proclaimed: “England is no longer a Christian Country.” Is it not similar in other so called Christian countries?

The original temple, templumor Temenoslost its meaning, for our hearts have grown cold, and our minds have lost touch with what is mysterious and sacred. As we have

impoverished the universe of the sacred, so we have impoverished ourselves. As we have turned sacred groves and other forests into the timber industry, we no longer have natural temples in which we could renew ourselves.

Towards a Spiritual Renewal

We are now reassessing the legacy of the entire technological civilization and what it has done to our souls and our forests. Our question is no longer how to manage our forests and our lives more efficiently in the pursuit of further material progress. We must now ask

We are now reassessing the legacy of the entire technological civilization and what it has done to our souls and our forests. Our question is no longer how to manage our forests and our lives more efficiently in the pursuit of further material progress. We must now ask

more fundamental questions: How can we renew ourselves spiritually? What is the path to a life that is whole? How can we survive as humane and compassionate beings? How can we maintain our spiritual and cultural heritage?

Wilderness areas, which I call life-giving areas, are important for three reasons. Firstly, they are important as sanctuaries. Various life forms might not have survived without them. Secondly, they are important as givers of timber that breathes, from which we can make beautiful panels and beams that breathe life into our homes.

Thirdly, and most significantly, they are important as human sanctuaries, as places of spiritual, biological and psychological renewal. As the chariot of progress which is the demon of ecological destruction moves on, we wipe out more and more sanctuaries. They disappear under the axe of man, are polluted by plastic environments, or are turned into Disneylands.

We have lost the meaning of the templum,and so our churches are deserted. We have to recreate this meaning from the foundations. We have to reintroduce the sacred into the world for otherwise our existence will be sterile. We live in an un-enchanted world. We have to embark on the journey of the re-enchantment of the world. We have to recreate rituals and special ceremonies through which the highest aspects of life are expressed and celebrated.

Forests still inspire us and infuse us with the sense of awe and mystery, if we have the time and quietness of mind to lose ourselves in them. And here is an important message. Forests may again become sacred places where great rituals of life are performed, and where the celebration of the uniqueness and mystery of life and the universe may take place. Making forests, places to reintroduce the sacred into the world, depends on our will. The first steps in this direction were taken by the famous Polish director, Jerzy Grotowski, who abandoned the theatre in order to make nature and particularly forests, the sacred grounds for man’s new communion with the cosmos.5

Let me finish with a short poem.

OF MEN AND FORESTS

Forests are the temples.

Trees are the altars.

We are the priests serving the forest gods.

We are also the priests serving the inner temple.

Treat yourself as if you were an inner temple

And you will come close

To the god which resides within.

To walk through the life as if you were

In one enormous temple,

This is the secret of grace.

NOTES

- Sir James Frazer, The Golden Bough, Vol. 2, p. 42.

- Seneka, Epistoles, 4, 12, 3.

- For further discussion see: J. Donald Hughes, “Sacred Groves: The Gods, Forest Protection, and Sustainable Yield in the Ancient World,” in ‘limo)? of Sustained Yield Forestry, N.K. Steen, Ed., 1983.

- For further discussion see: Madhav Gadgil and V.D. Vartak, “Sacred Groves in India – a Plea for Continued Conservation,” The Journal of Bombay Natural History Society, Vol. 72, No. 2,

- 314-320, 1975.

- See Jerzy Grotowski. On the Road to Active Culture, 1979; and his other writings.

Comments are closed.